City Hall

South Light Court

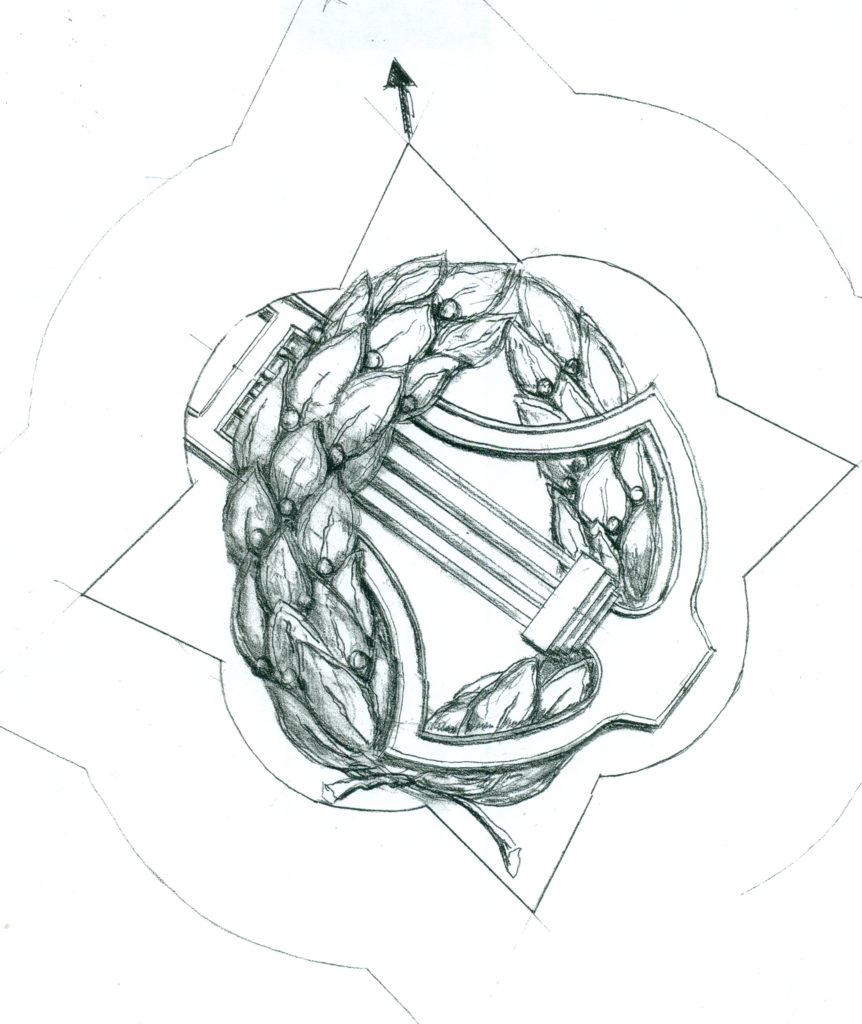

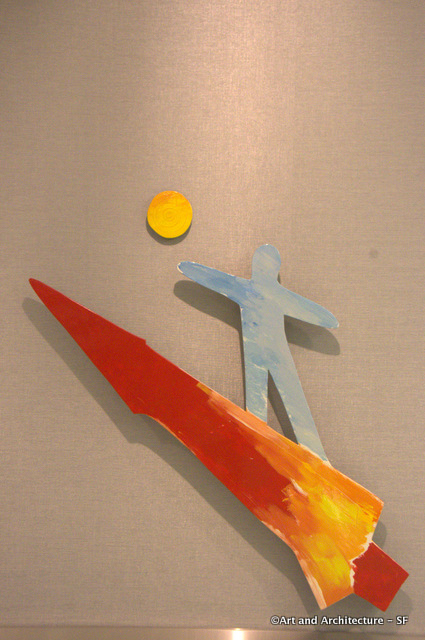

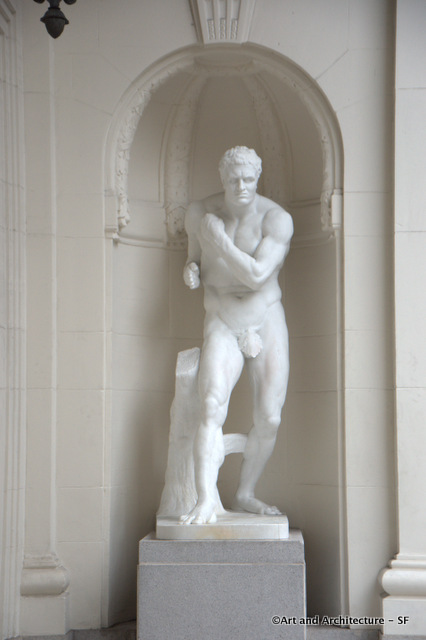

Goddess of Progress by F. Marion Wells

Goddess of Progress by F. Marion Wells

The plaque that accompanies her reads: On April 17, 1906, the dome atop San Francisco’s City Hall that was completed in 1896 supported a twenty foot statue by F. Marion Wells. The Goddess of Progress, with lightbulbs in her hair, held a torch aloft in her right hand, causing some contemporary counts to refer to it as the Goddess of Liberty. The statue was so securely mounted that on April 18, 1906, when City Hall and the city around it lay in ruins from the great earthquake-fire, it continued to stand at the peak of the now exposed steel tower. After workmen brought it down from the precarious perch when the building was finally torn down in 1909 the statue fell from a wagon and the 700-pound head broke off.

***

It is my understanding that the whereabouts of the body is unknown.

Photo courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library taken in 1906

Photo courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library taken in 1906

Francis Marion Wells was born in Pennsylvania in 1848. Wells arrived in San Francisco about 1870 and was a cofounder of the Bohemian Club in 1872. He was Douglas Tilden’s first teacher in 1883 and the following year was commissioned to do a bust of Hawaii’s King David Kalakua who was visiting in Oakland. Wells was active in the local art scene as a teacher as well as a producer of portrait busts and bas reliefs.

Once a very wealthy man, he fell on hard times, as this article from the San Francisco Call of July 14, 1903 attests:

FRANCIS MARION WELLS FORCED TO ENTER THE COUNTY HOSPITAL

Well-Known Sculptor, Artist, Literateur and Former Club Man, Afflicted by Illness, Compelled to Ask Municipality for Help

FRANCIS MARION WELLS, sculptor, literateur, club member and well-known man about town, was forced by dire illness and strain of circumstances to apply for admission to the City and County Hospital yesterday. He is now lying there in a helpless and pitiable state. Not one single friend came to him in his distress, although when in affluent circumstances his beautiful home and grounds at Berkeley were filled with those who enjoyed the royal hospitality that they were always welcome to there.

Broken in spirit, sick nigh unto death, his arms paralyzed, his mind partially deranged from his sufferings, he was compelled to seek the only relief at hand and become a ward of the city. His faithful wife has struggled nobly during his four months illness. He has been during all that time entirely, helpless, the result of five apoplectic shocks.

Two months ago, to save the family from actual starvation, Mrs. Wells took a position as housekeeper at the Vienna Lodging-house, 533 Broadway, where, with their two young sons, she was just enabled to make enough to keep the wolf from the door. As she had to do the entire work of twenty rooms and also cooking for the family, she had no time to give her husband the constant nursing that his case required, but was by his side whenever she could steal a moment from her work.

Yesterday afternoon when the ambulance came to take Wells away he said: “I hope there won’t be a crowd to see me put into the ambulance, as I don’t want the people to see me in this poverty stricken condition.” This was too much for his wife to bear, and she borrowed $2 from some kind neighbors, a hack was procured and the sufferer was, carried down the rickety stairs and placed in it. His wife and sons accompanied him, to the hospital and made him as comfortable there as possible and then bade him farewell and returned to their humble lodgings.

Mrs. Wells, who is a highly educated and refined Parisian, is broken hearted over the thought of his position.” She said with tears streaming down her pale face: “I do not care for myself; I am young and can work for my two boys, but to think that my husband’s friends should allow him to become a burden to the city is almost more than I can bear. When we were in deep distress, surrounded, by poverty and sickness, I wrote to several of his former wealthy, old-time and intimate friends in the Bohemian Club to come to his relief with food and medical attendance, but not one of them replied. I did not ask for anything for myself, only for him, and that appeal they refused him. Today he fainted four times on the way to the hospital, and when I left him he was almost, unconscious. Oh! I do not want him to die there. Don’t you think some of his old friends will do something for him and put him into a private sanitarium where his last hours can be spent?

RUINED BY SPECULATION.

“We have been very unfortunate.. When I came from Paris, fourteen years ago, I brought $60,000 with me and used it in buying property here and then built a beautiful home in Berkeley. All went well until General Ezeta persuaded us to go into his San Salvador scheme, and he was so persuasive that we put in $40,000— and we lost every cent of it.

Bad luck followed, we mortgaged our home; and lost it. Then I commenced to sell my jewels. My $8000 diamond necklace, which my mother gave me, I pawned for $1200. I had hoped to redeem it, although Mr. Shreve had offered to buy it for $5000. Little by little everything went, and now we are worse than penniless. My husband was always goodness itself to me, and we all love him dearly. My oldest son is 13. He has just ha, the misfortune to cut off the end of his finger. My youngest boy, Emanuel, is 11, and helps me as much as he can. “My husband is a member of the Universal Order of Knight Commanders of the Sun, and here are the original parchments granted him. I think he was also one of the charter members of the Bohemian Club. It is a very sad ending to the life of a man with a brilliant brain, with accomplishments and with so generous and kind a heart for all his friends.

He was born in Louisiana, his father being General Francis Marion Wells, but he was educated in the eastern part of Pennsylvania.

SCULPTOR OF LIBERTY. Marion Wells, as he was called, has been well known here for many years and has been one of the most prominent sculptors in the city. His statue of Liberty on the dome of the City Hall is a fine piece of work and a monument to his abilities. The figure is modeled from his wife and the poise is extremely graceful. The bas relief of John Lick, which was executed at the request of the Lick trustees, and now hangs in the Pioneer Hall, is a splendid likeness of the great philanthropist. The John Marshall monument in Sonora County, erected to commemorate the first discovery of gold in California, also exhibits great talents.

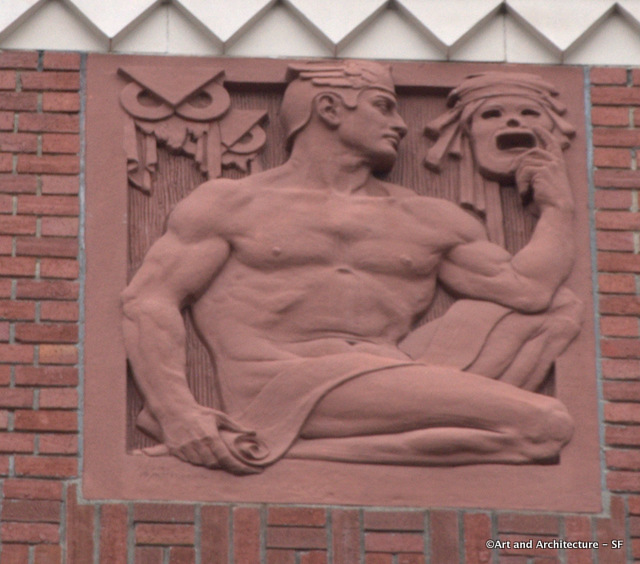

Among other works are the bears over the entrance to the First National Bank, which have marked merit in conception and design. He also did some artistic modeling for the Hibernia Bank, which adds much to the beauty of that handsome structure. The great owl which stands at the top of the grand stairway of the Bohemian Club is also of his handiwork. Other work which has been highly commented upon adorns St. Ignatius Church, the quadrangle and the memorial chapel at Stanford University.

***

Wells Died, July 22, 1903

The head suffered a few indignities on its way to the San Francisco City Hall Museum area.

The head was apparently given to John C. Irvine by former mayor James D. Phelan after it was removed from the old City Hall. It was, later, owned by his son, William Irvine.

It then came into possession of the South of Market Boys who gave it back to the city April 18, 1950, the 44th anniversary of the Great Earthquake.

It was later displayed in Golden Gate Park, then placed in storage.

Seven years later, in 1957, the head was sold, along with several cable cars, at public auction to Knott’s Berry Farm, a Southern California amusement park. It was given back to the city by Knott’s Berry Farm in the mid-1970s.

The goddess was, for many years, displayed at the Fire Department Museum, but was moved in 1993 to the Museum of the City of San Francisco. The goddess was then moved to City Hall in 1998 to celebrate the reopening of the structure after it was repaired following the 1989 earthquake.