The Embarcadero

The Ferry Building, built in 1898, sits at the foot of Market Street.

The Ferry Building, built in 1898, sits at the foot of Market Street.

In 1953, San Francisco proposed the Embarcadero Freeway that was to connect the Bay and Golden Gate Bridges. Construction started at the Bay Bridge end; after 1.2 miles of freeway were built, neighborhood organizations began to gather and oppose the project. In 1959 the Board of Supervisors voted to stop the construction, marking the first time a government body had ever taken such an action. For years, the stub of freeway running across the waterfront stood as a monument to both grand freeway construction and its opposition. In 1986 the Board of Supervisors put forth a new urban plan for the waterfront that included a measure to tear the freeway section down, but the voters, afraid of gridlock, rejected it. The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake changed everything.

The Embarcadero Freeway

The Embarcadero Freeway

After the earthquake, the California Department of Transportation proposed three scenarios: 1) retrofit the damaged freeway, 2) rebuild a depressed freeway or 3) demolish the freeway and replace it with a grade level street. The third choice was determined to be the wisest and most cost effective decision.

Demolition began and the revival of the waterfront became the mission of the Port of San Francisco and the Planning Department. The Port’s goal was to attract more people to the waterfront and to transform the area from an industrial service road serving the piers to a grand urban boulevard. The planning, which had begun in the 1980s, was revamped, and construction took place from 1993 to 2000.

Freeway deconstruction doesn’t occur often. As a result, there are not a lot of successful examples for designers and planners to learn from. The deconstruction process along what is now simply called The Embarcadero in San Francisco is ongoing. As the Port and city learn how the public utilizes the waterfront area, its redesign and reconstruction continuously evolves.

The Embarcadero runs under the San Francisco Bay Bridge.

The Embarcadero runs under the San Francisco Bay Bridge.

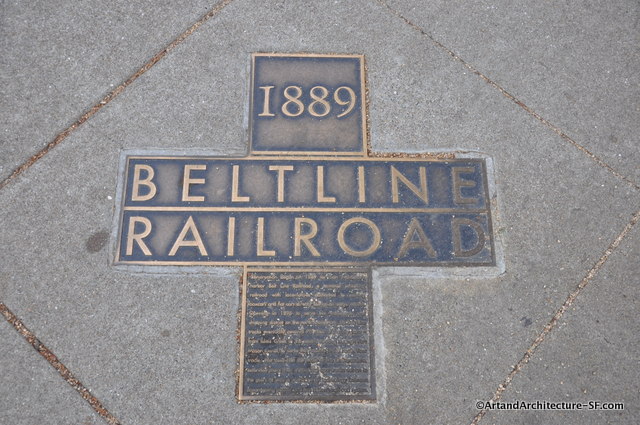

Art Ribbon, one of the first projects to bring design cohesion to the Embarcadero, was a collaboration between architects Vito Acconci, Stanley Saitowitz and Barbara Staufacher. Begun in 1991, it is two miles of lighted glass block set in paving. Due to extensive committee review and resulting modifications to the project, the architects complained Art Ribbon was not the grand idea that they thought the waterfront deserved.

Restaurants and art work are a vital part of the new Embarcadero. See Cupid’s Span

Restaurants and art work are a vital part of the new Embarcadero. See Cupid’s Span

Farmers Market at the Ferry Building

Farmers Market at the Ferry Building

Art Ribbon was not only the first step in the process of turning The Embarcadero into a grand boulevard, it was also a pioneering project in which various art and governmental agencies began learning how to interact and live with San Francisco’s vibrant skateboard community.

When Art Ribbon was first constructed, the skateboard community found the sharp edges and different lengths of concrete very appealing; however, chips started appearing almost immediately in the structure from the skateboards. The differing reactions of the architects mirrored the various responses from the community.

Saitowitz asked furiously, “Can’t you understand you’re ruining something that belongs to you, the people?” Solomon, however, responded differently, “I love it that the skateboarders love it, and Stanley hates it that the skateboarders love it.” She felt that skateboarder’s usage was “part of the world.” Acconci also supported the skateboarders with this statement: “Our goal is to make spaces that free people-to make devices and instruments that people can use to do what they’re not supposed to do, to go where they’re not supposed to go.”

Pig Ears on the raised portion of the Art Ribbon

Pig Ears on the raised portion of the Art Ribbon

In 1999 the debate once again become a front burner issue when the city installed SkateBlocks, or “pig ears,” as the police department calls them, on the raised concrete portions of the Ribbon. SkateBlocks are manufactured in Seattle, Washington, by a company called Ravensforge. They are 3-inch high metal brackets that mount onto a surface and are designed specifically to deter skaters and skateboarders.

In December of 1999 the San Francisco Chronicle received a letter to the editor with this comment from reader Caroline Finucane: “I contend that the clips are far uglier and distracting than the skateboard marks and that the kids are actually using the benches in the only way possible. Concrete benches at the water are cold. You can’t sit on them. The Art Commission should lighten up and look at the Art Ribbon as a work in progress, thanks to the skateboarders. By the way, I am a middle-aged lady with a bad leg and I do freeze in my tracks when I hear the kids rolling, but the joy of their riding … pleases me.” Finucane went on to say that the clips were “mean spirited.”

This type of dialogue continuously confronts designers of public spaces, but it also helps to define and redefine how public space is used. Grassroots movements initiated by local communities help designers and government officials stay on top of changing attitudes regarding public property.

In the coming years Art Ribbon will be altered. The present plans call for making much of the Ribbon flush with the promenade. This will essentially make it disappear. Is this just another iteration for the promenade, a spiteful gesture toward skateboarders or the beginning of banal, bland and committee-designed public space?